Starting from the end, and failing at building a startup

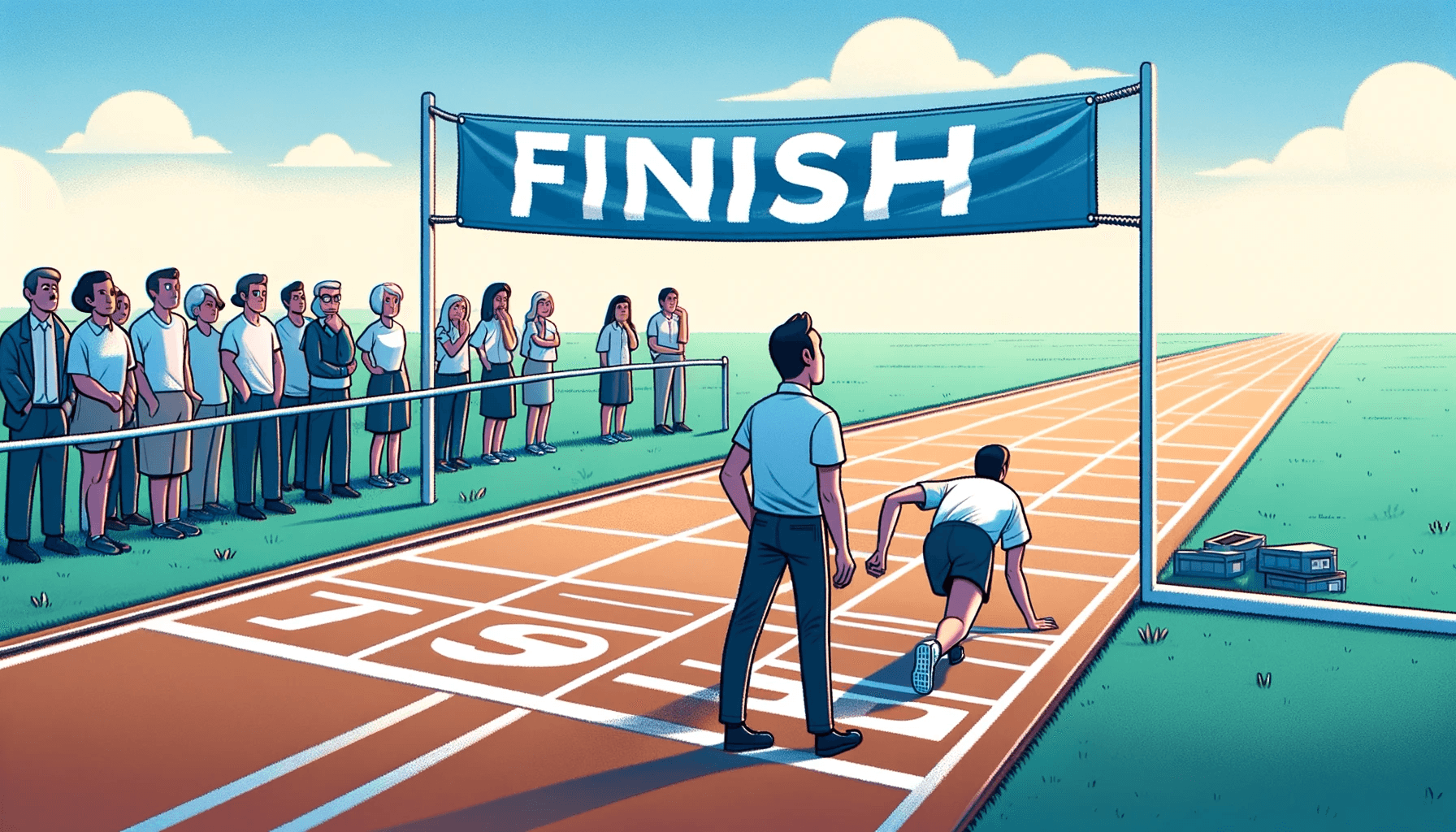

The end tends to be much sexier than the beginning. Think about it, when we set ourselves a new challenge, we immediately think about the most gratifying aspect of it.

Starting at university makes one think of those interesting projects one will be contributing towards. A first date takes one’s mind to the nights of intimacy. And building a product startup brings thoughts about thousands of people using one’s product.

The funniest bit is that one could be so involved in a current project, and so excited about the end, that the thought of “Hey, this doesn’t make sense” doesn’t come across for years.

These are some lessons from my story of how starting from the end when building my startup, Lagrange Systems, led us to failure.

The origin

A couple of years before starting Lagrange, I started advising +58 Gourmet, a Venezuelan bakery in Miami. As the bakery grew, new challenges emerged, including the rising payroll costs due to increased demand. Nevertheless, we knew, and a bit of statistical analysis confirmed, that there was plenty of idle capacity during a normal day that, if reduced, would keep payroll under control.

This kind of optimizations is where machine learning shines, so I sat down one weekend, built a forecasting model along with an optimization algorithm and voilá, we had data-driven schedules that set the foundation to reduce payroll expenses. So, we started testing…

And it worked!

Payroll costs were slashed by 15% in the first few months. We were up to something. We had to bring it to other restaurants.

We sorted out the financials, contacted a few people, assembled a team, and put our heads down to work to develop a great product that could scale to other restaurants. After all, the idea surged “organically” from a need of a real bakery, it had a real impact, and a real customer was happy. Thus, the idea was already validated.

Wrong.

A few successes are not enough to validate a concept

Nowadays, I believe that the correct way of thinking should have been more cautious. The fact that you got one or even a few people interested in your product, doesn’t mean that there is an accessible market for it.

Be especially cautious when one has a strong influence over those people. In the case of +58 Gourmet, I was already their advisor. They trusted me, I had access to their data, and I didn’t have to sell the solution. The sole fact of me bringing the problem up was enough for them to consider it as a potential problem.

This success story was far from a real market signal. A better way forward was to dismiss the success and focus on having conversations with my prospective clients to identify if there was any interest in an AI scheduling platform.

I not only jumped straight ahead to the end and used all resources to develop a product without a validated market, but I purposely delayed presenting the product to prospects because “it wasn’t ready”.

It is never “too early”

One should look for feedback from one’s target market before even considering it the target market. Even if there is no code, not even a slide deck, markets should be properly assessed before a business plan is in place.

I delayed showing the product to people because it was in its earliest stages, lacking lots of essential functionality, and I didn’t want to lose customers. Guess what, I couldn’t lose what I didn’t have.

In the context of B2B, initiating early conversations is crucial. While it's understandable if either party is not entirely prepared, keeping potential partners informed of your progress is vital. Neglecting these early discussions can result in considerable time spent developing features that may ultimately be deemed unnecessary or irrelevant to the core issues at hand.

Talk to people, listen to what they say and listen to what they don’t say. Test different advertising channels, and find your match based on research, not personal preference. Assert you can communicate with your target market and that they care about your message.

Develop your testing and validating process as soon as possible. The more you can test, the quicker you’ll learn.

From a personal standpoint, it is never too early. Build an audience. Start delivering as much value to as many people as possible. Share your learnings. Be useful. Be memorable. Take action.

Any other step would mean starting from the end.

Hard doesn’t begin to describe it

I don’t exaggerate when I say that building Lagrange Systems is the hardest project I’ve ever attempted. Having to step into all the different hats as the company required them made me live outside of my comfort zone during pretty much the whole journey.

A friend of mine says “It is not the same to think about the pain you’ll feel if you get shot, than feeling the pain of being shot”. The rollercoaster is real, and it is way steeper than anticipated.

Dedicating this amount of effort to a project can impose a huge toll on one’s personal life, especially if it comes tied to financial constraints. I was aware of this, but the pain of being shot still feels different. Triple-check you’re ok with sacrificing some of your personal relationships, hobbies and desires to lift the company off, you’ll need the reassurance.

What is life without a challenge?

“If you’re not growing, you’re shrinking”, and challenges are fuel to growth.

Just make sure your team remains exceptional, committed and can tolerate pain. The team makes or breaks a company. In the same spirit, if your teammates are not propelling the company, they’re pulling it back. If they’re not growing it, they’re shrinking it.

And most importantly. Have fun and faith. Fun with your project, your teammates, your tasks and your vision. Faith in that all the efforts are leading towards your goal, even when there’s no apparent progress being made.

This is a bit long already, so I’ll probably write one or two extra parts.

Best of lucks!