Evolving Deep Neural Networks

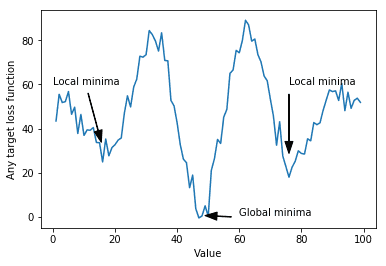

Many of us have seen Deep learning accomplishing huge success in a variety of fields in recent years, with most of it coming from their ability to automate the frequently tedious and difficult feature engineering phase by learning “hierarchical feature extractors” from data [2]. Also, as architecture design (i.e. the process of creating the shape and functionality of a neural network) happens to be a long and difficult process that has been mainly done manually, innovativeness is limited and most progress has come from old algorithms that have been performing remarkably well with nowadays computing resources and data [13]. Another issue is that Deep Neural Networks are mainly optimized by gradient following algorithms (e.g. SGD, RMSProp), which are a great resource to constraint the search space but is susceptible to get trapped by local optima, saddle points and noisy gradients, especially in dense solution areas such as reinforcement learning [6].

Illustration of a function with noisy gradients and several local minima. A gradient following algorithm such as SGD will get easily trapped by the local minima if it is initialized in a low (0–30) or high (65–100) value.

This article reviews how evolutionary algorithms have been proposed and tested as a competitive alternative to address the described problems.

Neural Architecture Search

As Deep Neural Networks (DNN) have become more successful, the demand for architecture engineering that allows better performance has been rising. With DNN increasing in complexity, the ability of humans to design them manually gets constrained and thus Neural Architecture Search (NAS) methods become more and more important. This problem gets particularly interesting when Sutton’s bitter lesson [15] is taken into account:

The biggest lesson that can be read from 70 years of AI research is that general methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin.

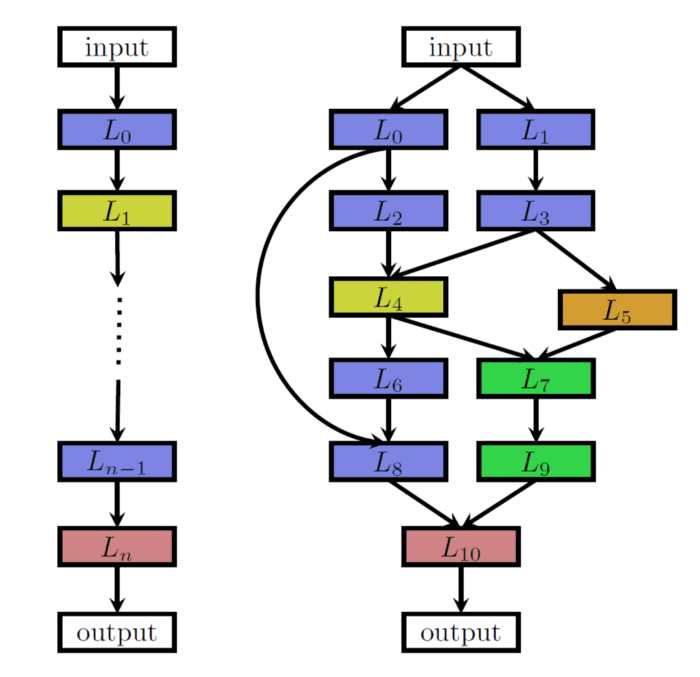

Evolutionary Algorithms (EA) have proven to be useful in this matter [10]. One might think of NAS as a three-dimensional process [2]. The first dimension is their search space, which defines the possible architectures that may be represented by the algorithm. Naturally, a bigger search space implies more possible combinations to be tested. In order to make the problem solvable, some constraints are straightforwardly implemented on layers:

- A maximum number of layers is selected.

- They may only be connected in a chain (sequential) or multi-branch configuration.

- Building blocks of layers types are predefined, but their hyperparameters may be tuned.

Chain connected (left) and multi-branch neural network (right) examples. Each node represents a layer and each arrow symbolizes the connection between them. Reprinted from Elsken et al. [2]. Next comes the search strategy, which defines how to explore the search space. Some common alternatives are Random Search, Bayesian Optimization, Reinforcement Learning, Gradient-based optimization and Neuro-evolutionary approaches. The first approach for evolutionary NAS comes from Miller et al. [7] who used genetic approaches to propose architectures and backpropagation to optimize weights. Then, Stanley and Risto [12] presented NeuroEvolution of Augmenting Topologies (NEAT), a Genetic Algorithm (GA) for evolving Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) that not only optimizes but also complexifies solutions by accounting for both fitness and diversity. More lately, Real et al. [9] found that evolution performs equally well than Reinforcement Learning in terms of accuracy, but it developed better mid-time performance and smaller models (further description on this case is given below).

Even so, both genetic algorithms and DNN are known for demanding high resources, in the order of thousands of GPU days. Therefore, for NAS to be an affordable strategy, performance estimation has to be conducted on lower fidelities (i.e. less certainty, by using an approximation) than the actual performance. Some examples on this are [11], that uses an ANN to predict the performance of candidate networks, approximating the Pareto-optimal front, and [8], by implementing a performance estimation strategy in which an LSTM neural network is used to estimate the validation score of another candidate neural network given only a few epochs of training. Instead of doing estimation, some approaches have tried to keep the functionality of the neural network while changing its architecture and thus speeding up training. Auto-Keras [5] has been built on this approach.

Applications of NAS to traditional neural network architectures has been researched in the last years producing a new state of the art result. To give some examples, Rawal et al.[8] proposed a tree-based encoding of a DNN that is searched through genetic programming and improved LSTM performance on based standard language modelling (i.e. predicting next word in a large language corpus) by 0.9 perplexity points (i.e. the new model now better estimates the target language distribution). Also, on image classification, Real et al. [9] evolve AmoebaNet-A to achieve 83.9% top-1, 96.6% top-5 ImageNet accuracy and thus establishing a new state of the art. It has been proposed that these results may be developed even further by taking advantage of diversity inherent in GA populations to amplify current ensembling methods and even encourage it explicitly, by directly rewarding ensembles into a population instead of direct models.

Evolving Reinforcement Learning

Neuroevolutionary algorithms may be split into those evolving both weights and architecture (e.g. NAS) and the ones that only try to optimize weights of a DNN. The combination of evolutionary algorithms with reinforcement learning generally comes as an only-weights implementation.

As in general gradient-based algorithms, such as Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) constraint exploration to gradient following, their search space becomes somewhat linear and local minima becomes a problem [1]. Furthermore, with Deep Reinforcement Learning (Deep RL) two extra issues arise: it is difficult to associate an action with a return when rewards are sparse, prematurely converging to local optima (i.e. they only happen after a series of decisions have been taken, also known as temporal credit assignment) [14] and they are very sensitive to hyperparameter selection [3].

Genetic Algorithms has been proposed as a workaround these issues in DRL. Such et al. [13] evolve the weights of a DNN with a gradient-free population-based GA and finds that it did well on hard Deep RL problems like Atari and Humanoid locomotion. By comparing their results with also a Random Search (RS), they find that GA always outperforms RS, and RS sometimes outperforms RL, suggesting that local optima, saddle points and noisy gradients are impeding the progress of gradient-based methods and that densely sampling in a region around the origin is, in some cases, sufficient to outperform gradient-based methods. They also find GA to develop substantially faster in wall-clock speed than Q-learning.

Such et al. [13] also point out that an unknown question is whether a hybrid approach that uses GA sampling in the early stages and then switching to gradient search will allow better and faster results. This is exactly what Khadka et al. [6] present with Evolutionary Reinforcement Learning (ERL), a hybrid algorithm that uses a population from an EA to train an RL agent and reinserts the agent in the population for fitness evaluation. They present GA as a good alternative to solve before mentioned Deep RL issues, but that also struggles to optimize a large number of parameters. Therefore, exploratory and temporal credit assignment ability of GA are combined with gradients from Deep RL to enable faster learning. Thus, Evolutionary RL is able to solve more tasks than, for example, Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) and faster than simple GA.

The bottom line

Practical studies like [6] and [9] have proven Evolutionary Deep Learning applications to be a useful method for advancing the state of the art. Nevertheless, lots of limitations are still present in employed methods, just like the use of predefined building blocks for NAS and non-crossover nor mutation used in ERL. Also, it is noticeable that EAs are seen as black-box optimization methods and thus they provide little understanding of why the performance is high.

Further research will decide the future of EAs in Deep Learning, but so far it seems that they are coming to stay and become an essential tool for solving specific learning problems, at least in the middle/long term.

References

- Aly, Ahmed, David Weikersdorfer, and Claire Delaunay (2019), “Optimizing deep neural networks with multiple search neuroevolution.” CoRR, abs/1901.05988.

- Elsken, Thomas, Jan Hendrik Metzen, and Frank Hutter (2018), “Neural architecture search: A survey.” CoRR, abs/1808.05377.

- Henderson, Peter, Riashat Islam, Philip Bachman, Joelle Pineau, Doina Precup, and David Meger (2018), “Deep reinforcement learning that matters.” In Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence.

- Hornby, Gregory S (2006), “Alps: the age-layered population structure for reducing the problem of premature convergence.” In Proceedings of the 8th annual conference on Genetic and evolutionary computation, 815–822, ACM.

- Jin, Haifeng, Qingquan Song, and Xigui Hu (2018), “Auto-keras: Efficient neural architecture search with network morphism.”

- Khadka, Shauharda and Kagan Tumer (2018), “Evolution-guided policy gradient in reinforcement learning.” In NeurIPS.

- Miller, Geoffrey F., Peter M. Todd, and Shailesh U. Hegde (1989), “Designing neural networks using genetic algorithms.” In ICGA.

- Rawal, Aditya and Risto Miikkulainen (2018), “From nodes to networks: Evolving recurrent neural networks.” CoRR, abs/1803.04439.

- Real, Esteban, Alok Aggarwal, Yanping Huang, and Quoc V Le (2019), “Regularized evolution for image classifier architecture search.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.01548.

- Salimans, Tim, Jonathan Ho, Xi Chen, and Ilya Sutskever (2017), “Evolution strategies as a scalable alternative to reinforcement learning.” CoRR, abs/1703.03864.

- Smithson, Sean C., Guang Yang, Warren J. Gross, and Brett H. Meyer (2016), “Neural networks designing neural networks: Multi-objective hyperparameter optimization.” 2016 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design (ICCAD), 1–8.

- Stanley, Kenneth O. and Risto Miikkulainen (2002), “Evolving neural networks through augmenting topologies.” Evolutionary Computation, 10, 99–127.

- Such, Felipe Petroski, Vashisht Madhavan, Edoardo Conti, Joel Lehman, Kenneth O. Stanley, and Jeff Clune (2017), “Deep neuroevolution: Genetic algorithms are a competitive alternative for training deep neural networks for reinforcement learning.” CoRR, abs/1712.06567.

- Sutton, Richard S, Andrew G Barto, et al. (1998), Introduction to reinforcement learning, volume 135. MIT Press Cambridge.

- Sutton, Richard (2019). The bitter lesson. Available at: http://www.incompleteideas.net/IncIdeas/BitterLesson.html [Accessed 13/05/19]

- Zoph, Barret, Vijay Vasudevan, Jonathon Shlens, and Quoc V Le (2018), “Learning transferable architectures for scalable image recognition.” In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 8697–8710.